Reliving Ishmael Bernal

National Artist for Film Ishmael Bernal

As a triumph of memory, happenstance, superb editorial work and design, it’s the most fascinating local book I’ve held in my hands of late — and it isn’t because I personally knew the subject, as well as the three co-authors (two of them posthumous).

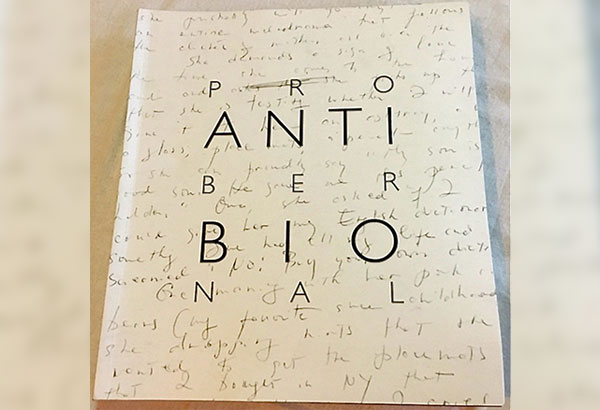

Pro Bernal Anti Bio is a 392-page softbound book in a handsome square format that allows the running main text to share space with mavelous marginalia from a legion of friends, writers and film people who had enjoyed association with the legendary film director Ishmael Bernal, who passed away in 1996 and was conferred the National Artist award in 2011.

Published by ABS-CBN Publishing, Inc. and launched on Nov. 25, it credits three co-authors: the subject himself, his life-long buddy Jorge Arago who passed away in 2015, and Angela Stuart-Santiago, in whose hands this testament to entwined lives, creativity and a memorable milieu became a labor of love enhanced by pluperfect strategic decisions.

“Ishma” or “Bernie” had asked Jorge to start preparing his biography, one that would focus equally on the biographer’s own life and their partnership. Jorge began to call it an anti-bio, and sporadically wrote essays that would frame the project. But time overtook them both, with a fire that hit Arago’s home laying waste to invaluable records.

Perhaps sensing his own mortality, Jorge tried to pass on the task to his friend Angela, who initially dismissed the daunting demand. Yet she found it falling squarely on her lap upon Jorge’s demise, especially when she learned that he had left sole access to his remaining private records.

Her “Pretext” introduces the book:

“The conversation between National Artist for Film Ishmael Bernal and rogue scholar Jorge Arago is mostly contrived but the words and sentiments are totally theirs, the threads fashioned from their own stories, published and unpublished, over the years.

“It’s a tell-all of a life lived to the hilt, fiercely forthright and critical but also gay and subversive, ironic and irreverent, sparing neither self nor nation, mothers nor lovers, art nor culture nor language, Marcos nor Cory. Friendly fire, as it were, in guerilla wars waged by two leftist intellectuals against ‘middle-class totems and taboos, innocence and igrorance.’

“I chime in now and then from the margins along with a cast of family, friends, artists, and critics in cameo roles. My backstory of the bosom buddies and the making of this anti-biography comes after, and Patrick Flores packs up with a paean to Ishmael’s ‘Awareness, Abandon.’”

Ishmael’s handwritten journal started in 1994 and Jorge’s essays form much of the conversation, with Angela allowing Jorge’s structural concept to hold sway in the early going. It starts with Ishma’s departure, then quickly flashes back to the start of their friendship in UP Diliman, cohabitation in a Malate apartment from where they published the counter-culture magazine Balthazar, and Ishma’s disastrous start as a movie director.

Covered as well in this period, from the 1960s to the ’70s, are the brief success with the bohemian When It’s A Gray November in Your Soul café on A. Mabini St., Ishma’s scholarship in France and film studies in Poona, India, his film reviewing days with The Manila Chronicle, aborted first film project, and breakthrough as a director with the critically acclaimed yet commercial flop Pagdating Sa Dulo.

He was lucky to have followed it up immediately with Daluyong, on which he writes:

“I was in the news a lot as — I don’t want to say it — the threat to Lino Brocka (the competition between (us) was always friendly). Considering that I had just had a box-office flop that was dubbed ‘artistic’ or ‘serious,’ I think the producers took a gamble. I could have given them another flop, but I didn’t.

“Daluyong became a big hit because it starred big bomba stars of the period: Alona Alegre, Rosanna Ortiz, Ronaldo Valdez, Eddie Garcia. It had enough sex, enough quotable quotes, enough long confrontation scenes and sampalan and iyakan. It had also lots of beautiful clothes and jewelry, beautiful cars, swimming pools, chandeliers, mansions.”

In culling their early memories together, a tongue-in-cheek mode was characteristically shared by Bernal and Arago, with both also questioning the “irrelevant erudition” they had been acquired.

At an rate, Ishma turned mainstrean, megging blockbuster hits, including a number of “bold movies” and the occasional artistic puzzler such as Nunal sa Tubig (script by Arago), until he peaked in the early 1980s with the controversial and eventually seminal Manila By Night, which became City After Dark when Imelda Marcos voiced out her objections. This was followed by a remarkable series of his best films: Relasyon with Vilma Santos and Christopher de Leon, Himala with Nora Aunor, Broken Marriage again with Santos and De Leon, and the comedies Working Girls 1 and 2 scripted by Amado Lacuesta, in whom Ishma found the ideal madcap partner. They also collaborated on the serious feminist film on abortion, Hinugot sa Langit.

In between were filler films for old producer friends, while the early activism that had helped galvanize his partnership with Arago also resurfaced, with the MTRCB and higher powers-that-be as the bogeys.

No less essential in providing a complete picture of this friendship are the pertinent explications and asides from co-author Stuart-Santiago. Deployed munificently are commentaries from contemporaries, colleagues, writers and film critics.

This roster alone is suitably impressive, counting among others Ninotchka Rosca, Nestor Torre, Petronilo Bn. Daroy, Joel David, Jose Maria Sison, Behn Cervantes, Anton Juan, Nick Deocoampo, Ed Cabagnot, Bernardo Bernardo, Mario Hernando, Bibsy Carballo, Ricky Lee, Pablo Tariman, Clodualdo del Mundo, Noel Vera, Rolando S. Tinio, Floy Quintos and Tom Agulto.

The women Ishma became closest to are also given frequent voice: non-showbiz friend Evelynne Horrilleno, film stars Rita Gomez, Elizabeth Oropesa, Nora Aunor and Vilma Santos, and scriptwriter Raquel Villavicencio. In the prime of his careeer, Ishma’s best lady buddy was fellow director Marilou Diaz Abaya.

The book also reveals the writing genius of Jorge Arago, whose quirky shyness would have deprived us of his brilliance if not for the text that is shared here, to wit:

“Since Bernal was conferred the National Artist Award, friends and relatives have not ceased to remind me that the honor calls for some changes in my perspective. I guess it means I cannot repeat Bernal’s considered opinion about who has the smallest tool in the film industry of his time, I must desist from identifying the venerable actor who found an ahas na bingi under his bed, I need crazy glue to prevent me from echoing Lino Brocka’s horrified scream of ‘Ecsta-NO!’ at the sight of a pro-active protrusion that had earlier driven Bernal to rave ‘Ecsta-SI!’ I may not speak, by the same token, about the difficulties he experienced in doing a short film for Amnesty International about the late unlamented Alex Boncayao Brigade and its pet peeves.

“But the National Artist Award itself, especially in the halcyon days BC (Before Caparas), is a safe subject on which I am free to abreact before fungi from Alzheimer’s overrode my memory entirely.”

On Bernal’s part, among his last entries that speak just as formidably of our society is the following:

“I look forward to making a film on the important participation of women in the revolution — Gregoria de Jesus, Marina Dizon, Narcisa Rizal, etc. Ramon Revilla is trying to pass a bill in Congress that will completely exempt from taxes all films about national heroes. If this bill is passed we might see a plethora of Andres Bonifacios and Gregorio del Pilars and Antonio Lunas and Mabinis. I don’t know if this is going to be good for the industry or not. (Laughs.) A massacre movie about Juan Luna and that woman! We do have a tendency to overdo things. It boggles the mind.”

Orders for the book, which sells for P900 a copy, may be addressed to bernalbynight@gmail.com.